A disorderly climate transition will exacerbate inequalities

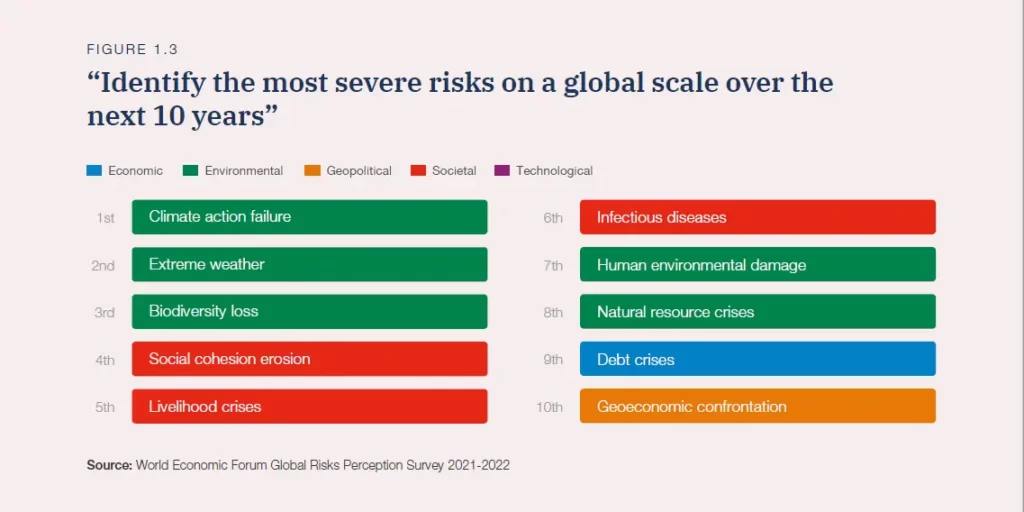

Respondents to the Global Risks Perception Survey rank “climate action failure” as the number one long-term threat to the world and the risk with potentially the most severe impacts over the next decade. Climate change is already manifesting rapidly in the form of droughts, fires, floods, resource scarcity and species loss, among other impacts. In 2020, multiple cities around the world experienced extreme temperatures not seen for years — such as a record high of 42.7°C in Madrid and a 72-year low of -19°C in Dallas, and regions like the Arctic Circle have averaged summer temperatures 10°C higher than in prior years. Governments, businesses and societies are facing increasing pressure to thwart the worst consequences. Yet a disorderly climate transition characterized by divergent trajectories worldwide and across sectors will further drive apart countries and bifurcate societies, creating barriers to cooperation.

Given the complexities of technological, economic and societal change at this scale, and the insufficient nature of current commitments, it is likely that any transition that achieves the net zero goal by 2050 will be disorderly. While COVID-19 lockdowns saw a global dip in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, upward trajectories soon resumed: the GHG emission rate rose faster in 2020 than the average over the last decade. Countries continuing down the path of reliance on carbon-intensive sectors risk losing competitive advantage through a higher cost of carbon, reduced resilience, failure to keep up with technological innovation and limited leverage in trade agreements. Yet shifting away from carbon-intense industries, which currently employ millions of workers, will trigger economic volatility, deepen unemployment and increase societal and geopolitical tensions. Adopting hasty environmental policies will also have unintended consequences for nature — there are still many unknown risks from deploying untested biotechnical and geoengineering technologies — while lack of public support for land use transitions or new pricing schemes will create political complications that further slow action. A transition that fails to account for societal implications will exacerbate inequalities within and between countries, heightening geopolitical frictions.

Risk of climate action failure

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) succeeded in getting 197 countries to align on the Glasgow Climate Pact and other landmark pledges (see Box 1.1 below), but even these new commitments are expected to miss the 1.5°C goal established in the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement and increase the risks from a disorderly climate transition (see Chapter 2).

The economic overhang of the COVID-19 crisis and weakened social cohesion — in advanced and developing economies alike — may further limit the financial and political capital available for stronger climate action. The European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States, for example, were reluctant to commit to a formal climate finance target to respond to worsening climate change impacts in developing country Parties. China and India lobbied to change the Pact’s wording from “phase out” to “phase down” of “unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

The economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic risks delaying efforts to tackle climate change by encouraging countries to prioritize short-term measures to restore economic growth, regardless of their impact on the climate, over pursuing green transitions. Brazil, for example, joined the other 140 countries responsible for 91% of the Earth’s forests in endorsing the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, even as deforestation in the Amazon accelerated to a 15-year high in 2021 following the pandemic-induced recession of 2020. Geopolitical tensions and nation-first postures will also complicate climate action. COP26 revealed heightened tensions on climate damage compensation, with affected countries facing pushback from large emitters, including the United States.

Climate change continues to be perceived as the gravest threat to humanity. GRPS respondents rate “climate action failure” as the risk with potential to inflict the most damage at a global scale over the next decade (see Figure 1.3). However, EOS results hint at divergent senses of urgency between regions and countries. “Climate action failure” ranks 2nd as a short-term risk in the United States but 23rd in China—the two countries that are the world’s largest CO2 emitters. In addition to its 2nd place rank in the United States, it ranks among the top 10 short-term risks in 11 other G20 economies.

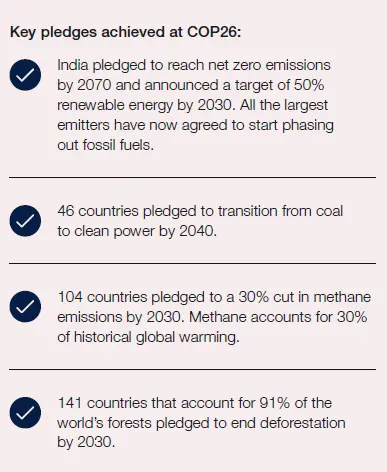

BOX 1.1 – Outcomes of COP26 and COP15

The 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26, held in Glasgow, the United Kingdom), which passed the Glasgow Climate Pact,1 concluded with important steps towards the 1.5°C scenario: it requested governments from 153 countries to update and strengthen their nationally determined contributions (NDCs), bolstered climate adaptation finance efforts, and continued the mobilization of billions of US dollars for climate funding and trillions to be reallocated by private institutions and central banks towards global net zero. COP26 was the first with financial sector attendance, represented by the Global Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), whose members manage over US$130 trillion in assets and already actively fund sustainable investments.2

For the first time, the Pact made explicit mention of the importance of transitioning away from coal—but did not commit to “phase out” inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. However, as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)’s Emissions Gap Report 2021 shows, reaching the 1.5°C target remains unlikely.3

Another key outcome was an agreement on the fundamental norms related to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement (on carbon markets), making it now fully operational.4 Businesses and governments also agreed on more aggressive investment in clean technologies,5 including a faster transition to electric vehicles and landmark pledges on methane emissions and deforestation.6

Key pledges achieved at COP26:

India pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2070 and announced a target of 50% renewable energy by 2030. All the largest emitters have now agreed to start phasing out fossil fuels.

46 countries pledged to transition from coal to clean power by 2040.

104 countries pledged to a 30% cut in methane emissions by 2030. Methane accounts for 30% of historical global warming.

141 countries that account for 91% of the world’s forests pledged to end deforestation by 2030.

The 2021 Conference of the Parties for the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15, held in Kunming, China) resulted in “strong declarations for safeguarding life on Earth”,7 along with joint measures for conservation actions and addressing unsustainable production and consumption;8 it also paved the way to negotiate a post-2020 global biodiversity framework for part two of COP15 in May 2022.9

Footnotes

1 UNFCCC. Decision -/CP.26, Advance unedited version. https:// unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cop26_auv_2f_cover_ decision.pdf

2 UNEP. 2021. “Emissions Gap Report 2021. Addendum to the Emissions Gap Report 2021.” Report. UNEP. 2021. https://wedocs. unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/37350/AddEGR21.pdf

3 UN Climate Change Conference UK2021. 2021a. COP26 The Glasgow Climate Pact. November 2021. https://ukcop26.org/ wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf

4 UNFCC. 2021. “COP26 Reaches Consensus on Key Actions to Address Climate Change”. UN Climate Press Release. 13 November 2021. https://unfccc.int/news/cop26-reachesconsensus- on-key-actions-to-address-climate-change

5 GFANZ. 2021. Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. https:// www.gfanzero.com/

6 European Commission. 2021. Launch by United States, the European Union, and Partners of the Global Methane Pledge to Keep 1.5C Within Reach. European Commission. Statement. 2 November 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/ detail/en/statement_21_5766 ; UN Climate Change Conference UK2021. 2021. “Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forest and Land Use”. 2 November 2021. https://ukcop26.org/glasgowleaders- declaration-on-forests-and-land-use/

7 WWF. 2021. WWF reaction to the adoption of the Kunming Declaration at COP15. World Wildlife Fund. 13 October 2021. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?3962441/WWF-reaction-tothe- adoption-of-the-Kunming-Declaration-at-COP15

8 IUCN. 2021. IUCN closing statement – part one of the UN Biodiversity Conference. 18 October 2021. https://www.iucn.org/ news/secretariat/202110/iucn-closing-statement-part-one-unbiodiversity-conference

9 Convention on Biological Diversity. 2021. “Part one of UN Biodiversity Conference closes, sets stage for adoption of post2020 global biodiversity framework at resumption in 2022”. Press Release. 15 October 2021. https://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2021/ pr-2021-10-15-cop15-en.pdf

Download the full World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2022

Source

Image Source

Tags: Global Risks Perception Survey, The Global Risks - Report 2022, World Economic Forum